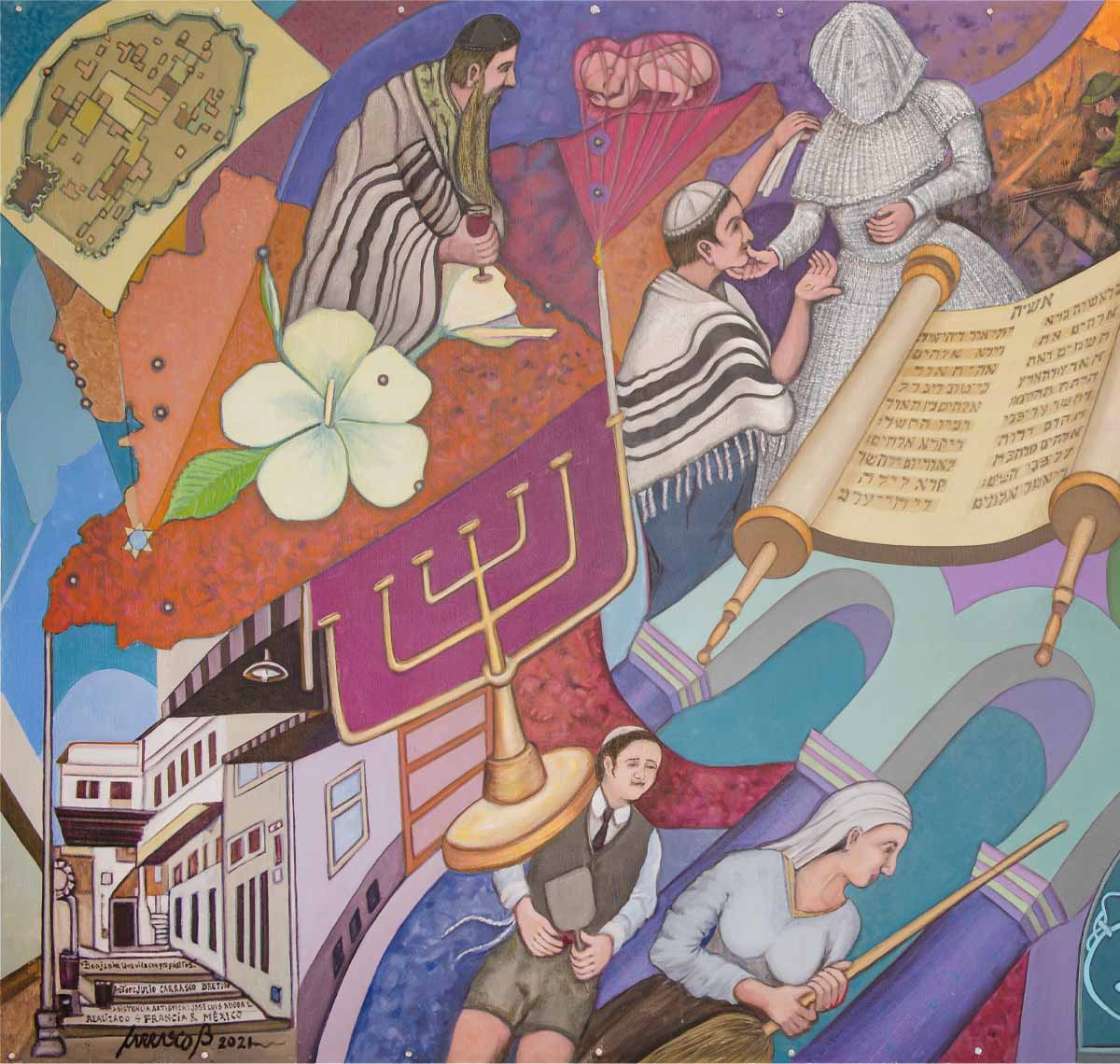

The mural starts on the left, with a plan from Damasco’s ghetto, from which a Star of David emerges and is placed on Syria’s map; it’s possible to place the main cities of this nation. A jasmine flower, Damasco’s symbol, is fixed on the map. Right away, Syria’s map works as a supporting table for a rabbi that is holding a cup, representing the marriage of Benjamín’s grandfather with a picture of Abraham and Sarah in the moment where he is giving her the wedding ring. Towards the bottom left corner, we can see the Damascan street where his grandparents lived; next to the alley is a menorah candelabra with only one candle on, symbolizing that out of seven children only Benjamín’s father, Itzhak, survived. For this very reason, we can see a baby on top; the grandfather died and grandmother Sarah was left a widow with seven kids. To support them, she works cleaning the synagogue, that is why we see a scene with Benjamín’s father helping his grandmother in the cleaning-temple chores; that is also why the synagogue is presented with columns and arches.

Over these arches is the Torah, indicating the religious influence in Benjamín’s father, who spent a lot of time in the synagogue and was profoundly interested in the religion and sacred scriptures from a young age, until he ultimately became a rabbi. Moving upwards, the soldiers in the trenches are representing World War I, where six of Itzhak’s brothers died of starvation and diseases. On the Torah’s right side, we can find a diagram that stands for Itzhak’s marriage to Neshla Duek, daughter of rabbi Yosef and Esther. This young marriage begot six children (it’s important to note the coincidence between the six brothers that died and the six descendants after that): Abraham, Sarah, Benjamín, his twin brother Yoseph, Moshe, and Esther.

The genealogical representation is detailed through a twisted branch in the case of Benjamín and his twin brother: one of the ends of the branch ends in a fruit, where Benjamín is pictured with his back toward us. This shows he was a diligent kid; he helped a classmate from a well-placed family to study, and everytime he taught him a lesson, he was offered fruit, which he shared with his siblings when he got back to his home, because for his family eating fruit every day was a luxury. The book Benjamín is reading contains the qualities that distinguished him his whole life, written in Hebrew: He was noble, with a generous heart, loving toward the other, attentive of the ones in need, careful, with sensibility, frank, kind, happy for others’ successes, modest, and humble.

Towards the top, we see the corner of a tailor shop due to Benjamín’s incursion to this trade when he was 15 years old, which allowed him to know the quality, use, and confection of fabrics. Under the genealogical diagram Benjamín’s birthdate is written in Hebrew; according to the Hebrew calendar, 22 Kislev 5694 would correspond with December 10, 1933, in the Gregorian calendar; this date is under the cosmic constellation of Sagittarius, that’s why there’s another symbol: the representation of man in the diagram.

Under this, the splendid door from the synagogue The Mnasha, forged with spirals and arborescences, points to the terrorist attack perpetrated on a Friday night during the Sabbath prayers, which ended with the life of over 70 people. This event coincided with Israel’s independence, on May 14, 1948. This terrible incident marked Benjamín’s life who, despite the pain of separating from his family, decided, as many young members of his community did, to form the second great migration of Syrian Jewish people. This painful exodus to Israel is illustrated in the mural with a panoramic image of the Golan Heights.

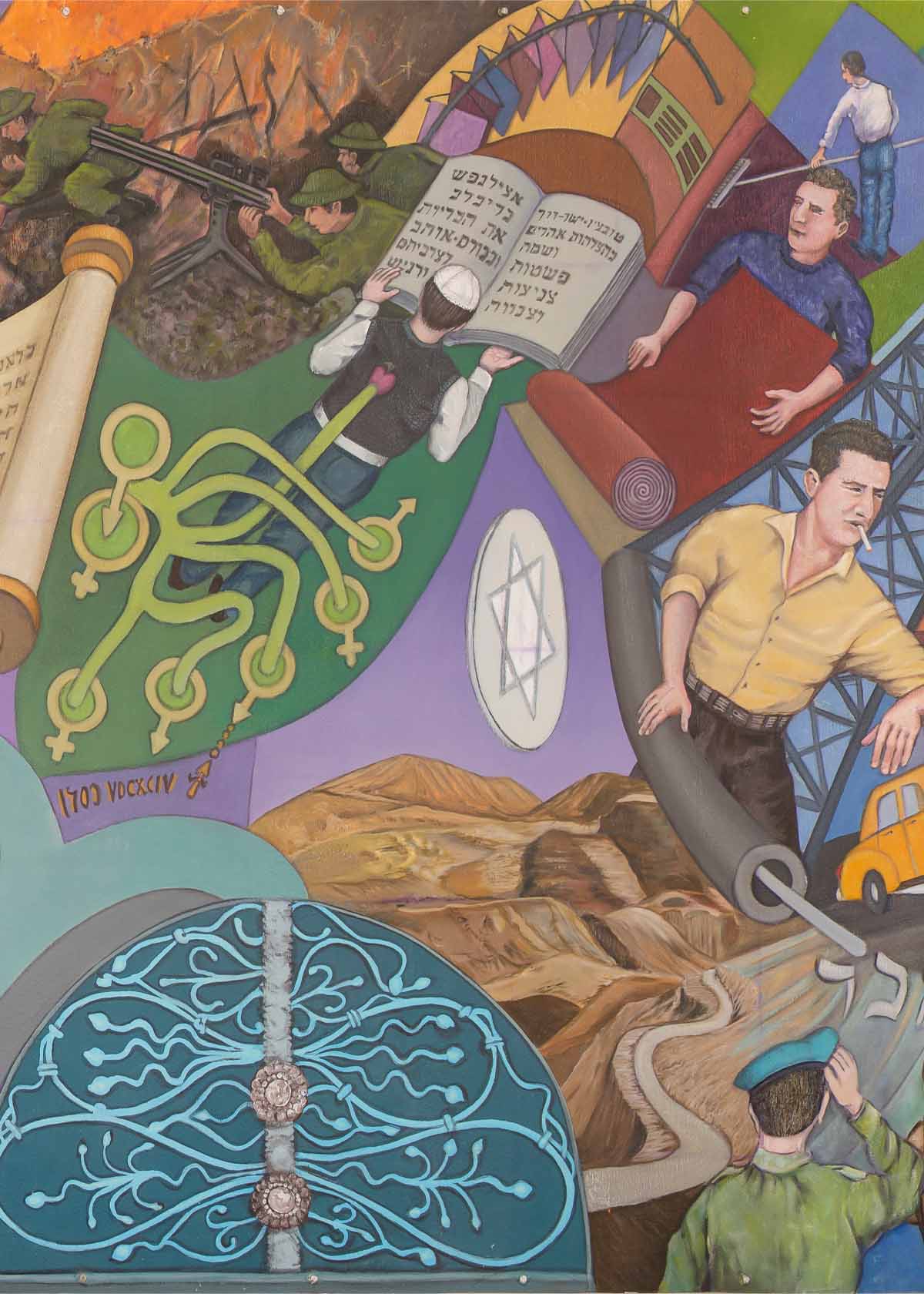

The young soldier giving his back to us is a representation of Benjamín, who enrolled in the Isreali army for three years in the Independence defense brigades. That is why he’s facing backwards and doing the loyalty military sign—it highlights the particularity of taking part in this historic feat.

On top of the Golan Heights is the Star of David to show the faith that characterized Benjamín his whole life; a faith that made him follow an ethical path in his actions and relationships, always remaining faithful to his Hebrew origins. Two scenes next to the Star show the main activities that he pursued during his stay in Israel: First, he was a worker in a petrol company. In 1952, the National Oil company was fracking in Lake Tiberias, the Dead Sea, Heletz, and Negev. As Benjamín was short, he was in charge of climbing to the top of the tower to adjust the coupling and the assembly of the extraction tubes. This fact is showcased with Benjamín touching a tube and, behind him, a typical fracking tower looking for oil. Next to this picture, we see two workers waterproofing rooftops: They’re Benjamín and his brother Moshe, who caught up with him in Israel. This was his second job of relevance during that time; above the waterproofing felt is the map of Israel.

The oil tower is pointing to the Venezuelan coat of arms: Benjamín decided to accept an acquaintance’s invitation to work in Caracas and set a textile fabric in motion in 1955. This man paid for his trip, but, upon arrival at Venezuela, Benjamín realized that the man wanted him to marry his daughter. Benjamín worked and lived in the fabric for six months, until it was fully working, without earning a penny. His stay at the fabric is illustrated at the right side of the Venezuelan coat of arms. When Benjamín let the owner know about his departure and asked for his money, the latter told him that what he had earned was the payment for his airfare and lodging, so Benjamín decided to leave. An Arab friend, owner of a restaurant, encouraged him to look for another job and offered his house. There, Benjamín fell in love with his daughter; this story is told in the mural through the Arab words restaurant and relationship, under the Venezuelan coat of arms.

Going downwards, we can see a box with a Star of David, which has a shirt coming out of it, representing Benjamín’s encounter with a man from Damasco that had a shirt store. Benjamín entered the shirt-selling business with such great success that he bought a car, the one that’s painted under the shirt. Next to Benjamín facing backwards dressed in military uniform is a box for cleaning shoes; more than a work tool, this is a wonderful Syrian craft, an object that Benjamín brought with him during one of his trips to Damasco, as a token symbolizing that, had he not left Syria, that would have been his fate. The car is painted as if it were going down a slope, which symbolizes the decision to give up the path treaded in Venezuela, particularly for a relationship that would go against his Jewish roots. Right next to the military beret, we can see a Hebrew word: friend; this is a reference to Raful Cameo, a Syrian friend that invited Benjamín to move to Mexico City (which map is on display to represent this trip as a transcendent option) in 1957.

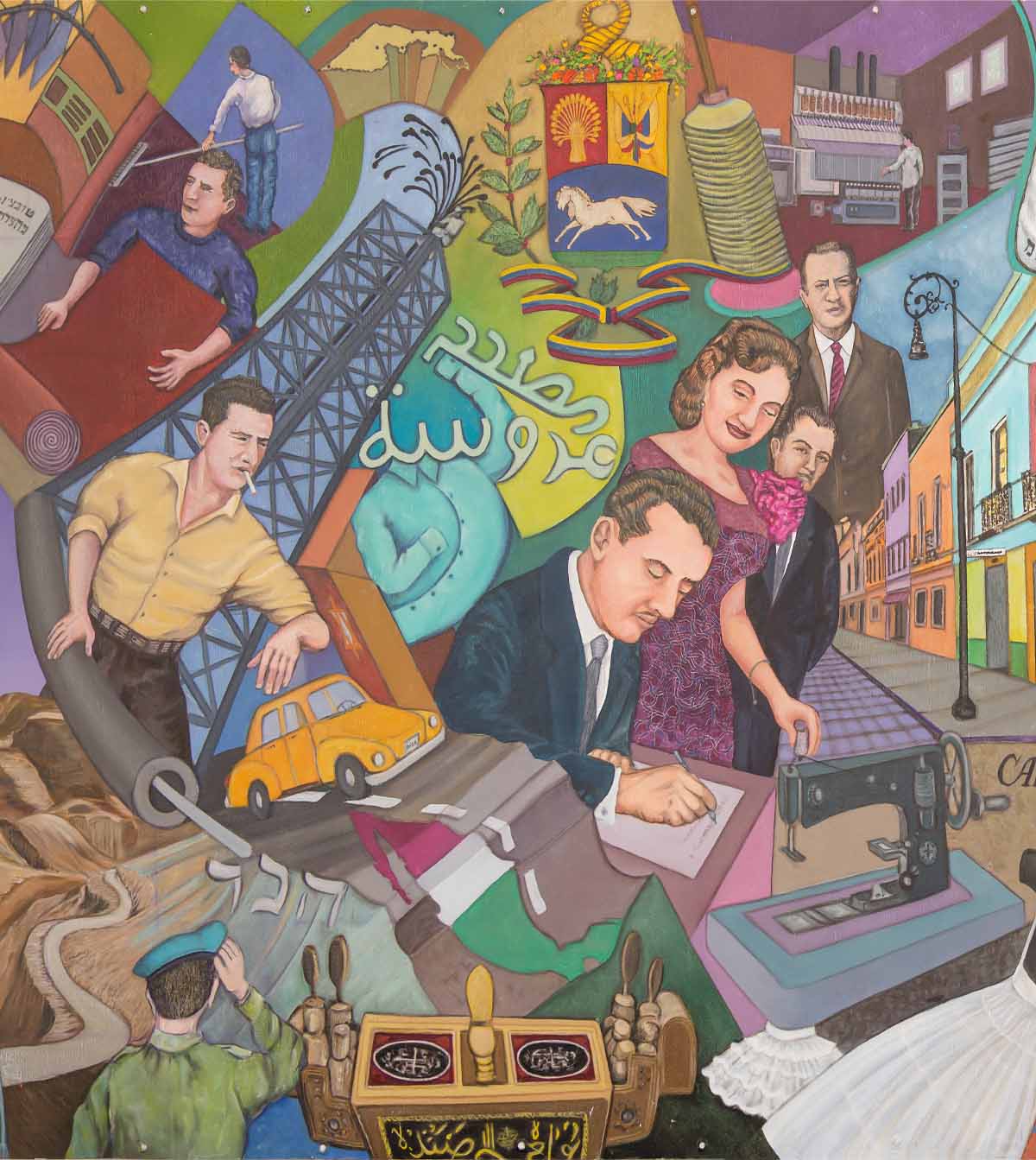

In the same year that Benjamín arrived to Mexico City, he got married; that is why we see the scene with Benjamín signing the certificate and Rebeca Farca Romano, his wife, smiling next to him in an upward direction. Benjamín fell in love with her, and she was the niece of his friend Raful, pictured behind her with another friend, Jack Penhos, who would become Benjamín’s business partner later on.

Next to this scene, we can see the street la Academia, where the first crinoline fabric was settled, in downtown Mexico City. Moving up, we can find the young face of his brother Moshe, who was always close to him, both in Israel and Mexico. Under him, we can see the Carnaval’s logo, Benjamín’s and Moshe’s children-clothes fabric, which they founded in association with Jack Penthos and his kids Isaac and Marcos.

To the right side of the fabric in la Academia street, there’s an alley from Safed. This image is interesting because it symbolized the beginning of a new chapter: Benjamín dared to open a company in Israel in 1963, but it did not prosper due to the economic conditions of the time. Benjamín decided to go back to Mexico in 1965. The sewing machine represents the gift that his parents-in-law, Abraham Farca and Bulin Romano, gave to him. With this machine Rebeca and him made crinolines, which they sold in markets at first. The mannequin stand for the transition from crinoline production to women’s intimate clothing, when Benjamín separated from his Carnaval partners. With Moshe, he decided to restructure the company and call it Carnival, that’s why their logo is placed on top of the previous images. Years later they would get 50% of the actions of Warshow de México under another business name, which is depicted with the Lycratex logo. The rummy cards placed on top of the logo are a callback to Benjamín’s likeness of this game. Above them are a compass and a watch: Benjamín always said that, in life, direction was more important than time. The grill that is down them represents his love to do barbecues on the weekends. This item is placed next to a series of flags from different countries, which portray the commercial and friendly relationships that Benjamín had internationally.

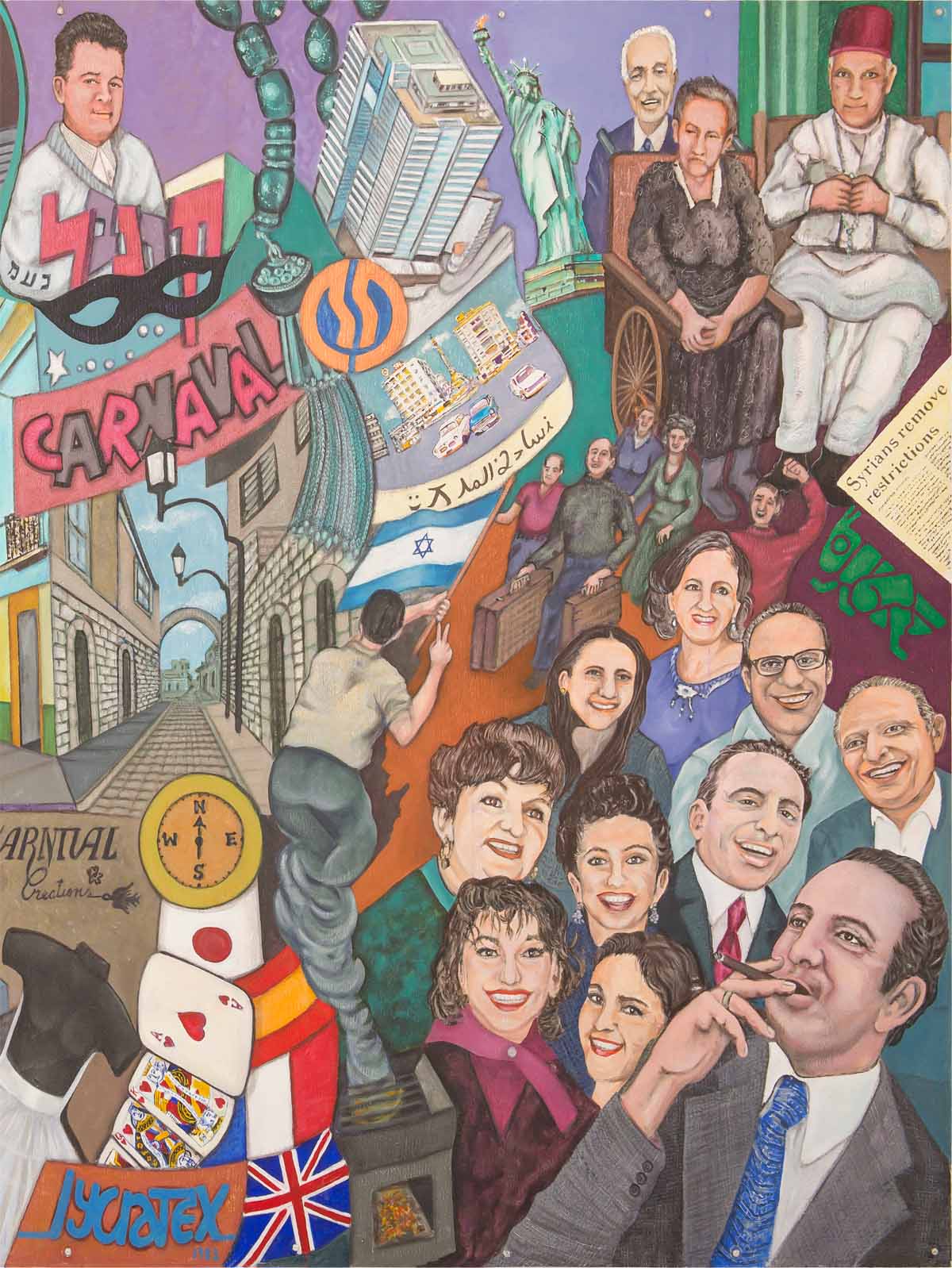

At the top, Moshe’s face has a masbaha next to it. Benjamín had it with him always, it was an important part of his reflections. On its right, we can see a building, which stands for the diversity his real estate businesses had. Under this is the logo of Assa, the industrial group that Benjamín consolidated. Further down is a postcard from Damasco’s public square, where Ely Cohen, Israeli spy, was hanged; under this image Martyr square is written in Arab. This fact happened before Benjamín embarked on his first trip to Damasco to see his parents and his siblings Yoseph and Esther; it had been 26 years since he had last seen them. It was dangerous to travel to Syria during that time, so he came up with a plan to make a secret trip in 1974. He looked for allies in the United States, the reason why the Statue of Liberty appears. Next to it, we can see the face of the Jewish community in Damasco’s president, Selim Totah, who collaborated with Benjamín in creating a relationship with the Syrian authorities in order to allow the trips that would let him see his parents and family in the future, along with allowing the visit of Syrian Jews that had emigrated from Damasco that wished to meet with their families. Thanks to the permit of arrival and departure from Syria, Benjamín helped thousands of fellow Jews to save themselves from future oppressions towards the Jewish community in Syria. Benjamín did a colossal task to reach his goal, going through several protocol interventions with letters from different authorities, including ones from the United States, England, Israel, Mexico, and Syria. Under the Statue of Liberty are various characters with suitcases, some of which moved to other countries such as Mexico and the U.S., but others moved to Israel, which is represented with a man facing backwards, next to the grill, waving the Israel flag.

It’s important to draw attention to the diaspora caused by Benjamín’s cunning, nobleness, and courage. In the top right corner are his parents: rabbi Itzhak, with a masbahana, and Neshla on a wheelchair. Under them is the headline of a London newspaper that talked about the good treatment the Damascan authorities had towards the members of the Jewish community: It was a lie, but it was part of Benjamín’s plan to befriend Syrian authorities and succeed in bringing immigrants together with their families. Between 1974 and 1976, thousands of Jewish people that lived in diaspora visited Damasco.

The grasshopper that’s under the newspaper is Chapultepec’s symbol, which represents the grievous death of Rebeca in 1976 after their second trip to Damasco with their children Isaac, Esther, and Sofía, and with their friends Jacobo and Cecilia Romano, and Salomón and Pola Saadía. The incident happened after a barbecue in Chapultepec to celebrate their homecoming from the trip, with the Farca and Romano families.

Benjamín became a widow with five children that were between 2 and 17 years old. Under the Statue of Liberty’s plinth second marriage is written in Hebrew, which signifies Benjamín’s second wedding, with Adela Masri Haber, who is on the left side of Neshla’s chair. Adela and Benjamín had three kids: Raquel and the twins José and David. In the mural, all of them are together to symbolize the union between them; they are depicted as a waterfall of faces that is led by rabbi Itzhak and Neshla. Next to Adela we can see Raquel’s and the twins’ faces; transversally, on the left, are Jenny, Esther, and towards the front, Sofía, Lucy América, and Isaac. Under Lucy América we find a detail of the Lycratex plant, located in Atizapán de Zaragoza. The mannequin has a double meaning: it alludes to the acquisition of Lartel from the Pliana Group in Tlaxcala, and, as with the flags, it represents the exportation of clothing, fabrics, and confections made by Lycratex. Benjamín did not only establish commercial international relationships, but he also made friendships throughout the world, which remember his honorableness and humbleness. He belongs to the kind of human beings that have accomplishments due to effort.

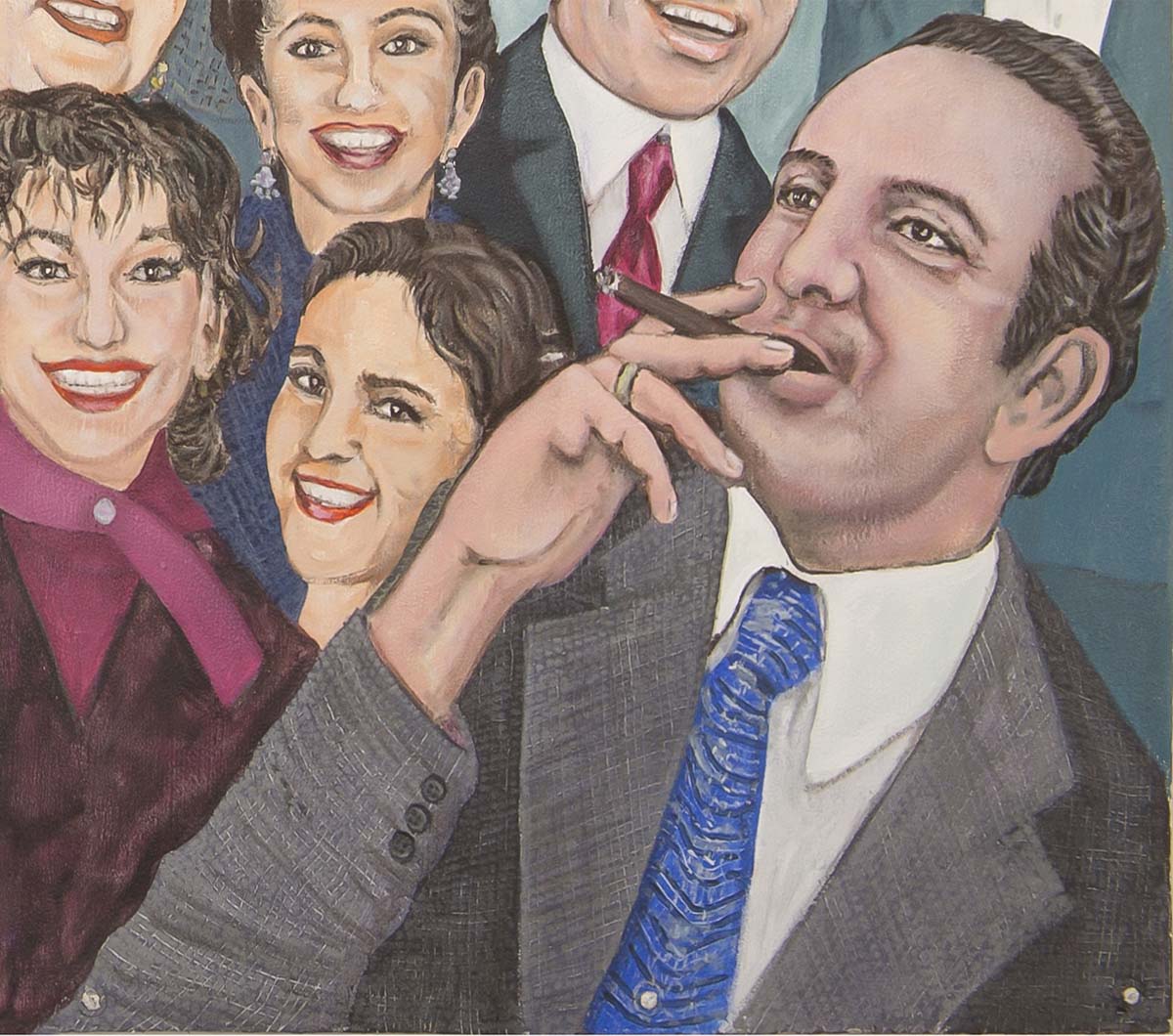

The mural ends with a partial effigy of Benjamín with a cigar while he’s laughing, as if he were looking at his life’s trajectory. We can see how, due to the mural’s composition, some of his children are looking at him, and they all have a smile of admiration.